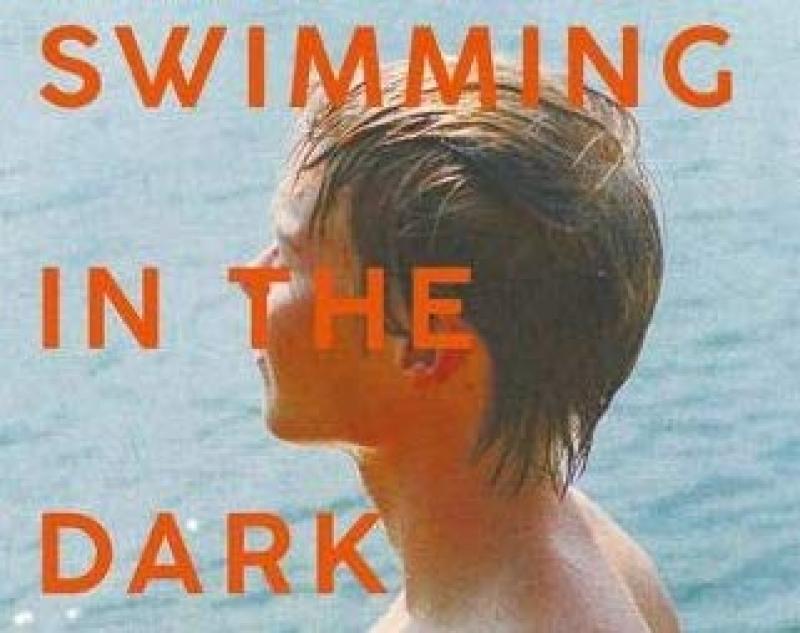

Tomasz Jedrowski: Swimming in the Dark review – of hypocrisy, both personal and systemic | reviews, news & interviews

Tomasz Jedrowski: Swimming in the Dark review – of hypocrisy, both personal and systemic

Tomasz Jedrowski: Swimming in the Dark review – of hypocrisy, both personal and systemic

Political parable on the collapse of communism in Poland turns on nostalgia for an illicit first love

Conjuring up nostalgia for a past readers never had is, perhaps, the litmus test for any good coming-of-age story. Writers have the hard task of making the general particular – because growing up, in one way or another, is universal whereas how and when and where we do is not. They also have the equally, if not harder, task of making the particular general – blurring that focus enough for the rest of us to share in their vision.

For his debut novel Swimming in the Dark, Tomasz Jedrowski manages to capture much of the graininess of his setting -– 1980s Poland in the iron grip of the Communist Party and later martial law – while conveying all the churn and throb and boom and bloom of innocence on the brink of experience; an innocence which for the 22-year old shy bibliophile Ludwik seems to extend beyond the beginnings of his first relationship, with the self-assured and problematically patriotic Janusz.

The two meet on a state-enforced agricultural retreat where for a week, along with a troupe of other graduands, they are tasked with uprooting beets for hours on end. The punishing midsummer heat turns into a sort of blessing when the seemingly uninterested Janusz asks Ludwik on a trip to Poland’s lake district before starting his job in the Office of “Press Control” (in the heaviest of inverted commas).

The writing renders this political excursion a romantic idyll – a sort of impressionistic painting, all dappled light and liquid – as we watch the pair dip in and out of bodies of water and frolic and “struggle”, to use Jedrowski’s foreboding euphemism, on the forest floor. It is not long before the spell is broken, as we imagined and as the novel forewarns us: the whole narrative is framed as a long questioning message from the slightly older, New-York based Ludwik as he watches the disintegration of the Eastern Bloc from afar and wonders what part Janusz – whose name sounds like the Polish for “I knife” – has to play in it all.

The writing renders this political excursion a romantic idyll – a sort of impressionistic painting, all dappled light and liquid – as we watch the pair dip in and out of bodies of water and frolic and “struggle”, to use Jedrowski’s foreboding euphemism, on the forest floor. It is not long before the spell is broken, as we imagined and as the novel forewarns us: the whole narrative is framed as a long questioning message from the slightly older, New-York based Ludwik as he watches the disintegration of the Eastern Bloc from afar and wonders what part Janusz – whose name sounds like the Polish for “I knife” – has to play in it all.

As the two make their inevitable journey from Arcadia back to Warsaw, their illicit (while not, as the book claims, illegal) relationship is in constant danger of interception by the ruling Party and its heirs. Hania, the flirtatious and beguilingly Westernised daughter of a government official, manages to drive an increasingly big wedge between them. The narrative fabric is also rent by particular moments from Ludwik’s childhood where, under his mother and grandmother’s tutelage, he first glimpsed the full horrors of Polish and European history.

This quietly clever double time scheme allows Jedrowski to underline the book’s real theme: hypocrisy, both of systems and individuals. The duplicity is in the book’s title, which stands for both the closeted Ludwik’s ideal anonymity – swimming “fearless and free and invisible in the brilliant dark” (and only there) – as well as a metaphor for the state of the Polish nation, politically floundering and “wading through the bog towards some new workable truth”.

Jedrowski is slightly better on the carefree former than the latter. Ludwik’s one attempt at political protest has a 99 Luftballons giddiness and even his wobbles have a sort of pleasurable decadent shudder to them. At other times, his touch seems like an inversion of Midas’s: all that’s solid melts or dissolves (Jedrowski’s favourite sensations). Those hushed-up history lessons become “terrible truth-spills” and there are a few slippery similes: a pair of panties are “white and lacy, discarded like someone’s fantasy” and a lake is “lined by high grasses like a secret”.

That touch, though, is seductive. And shored up against the occasionally ill-defined moment are some brilliant set pieces – particularly a house party Hania hosts which rocks to a smuggled soundtrack of Serge Gainsbourg, Blondie and Nico’s “low, titanic voice” in a sort of heady wash and swell reinvigorating the phrase New Wave (and which doubtless shares some DNA with the recent film, also set in the 80s, Call Me By Your Name).

Swimming in the Dark, in its angrier moments, might not burn with fire of a James Baldwin novel (Ludwik and Janusz bond over a contraband copy of Giovanni’s Room) but it does have the power to cast us back to, and perhaps even yearn, for the past. Even one we may have never had.

- Swimming in the Dark by Tomasz Jedrowski (Bloomsbury, £14.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Add comment