Christmas Book: When Broadway Went to Hollywood | reviews, news & interviews

Christmas Book: When Broadway Went to Hollywood

Christmas Book: When Broadway Went to Hollywood

Ethan Mordden's latest opinionated guide has plenty of entertainment value

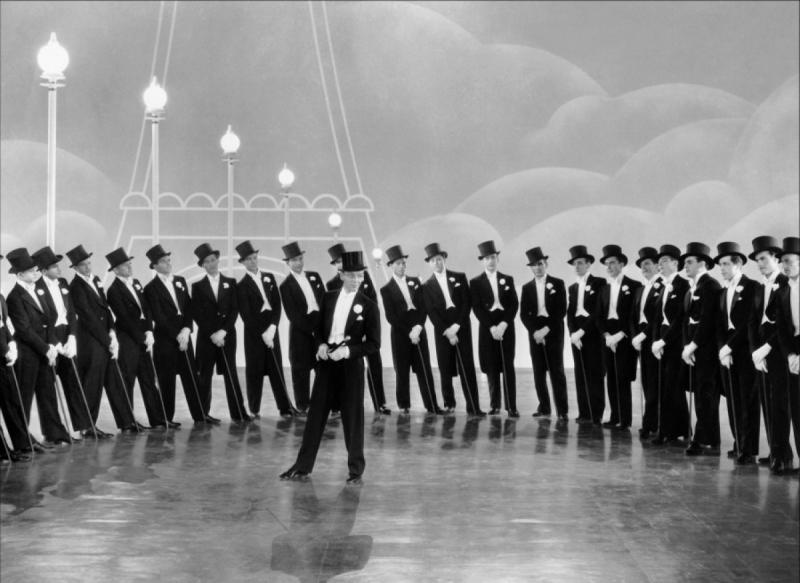

Tinseltown's relationship to its more sophisticated, older New York brother is analogous to Ethan Mordden's engagement by Oxford University Press. The presentation is a sober, if slim, academic tome with an austere assemblage of black-and-white photos in the middle; what we get in the text is undoubtedly erudite but also racy, gossipy, anecdotal, list-inclined, sometimes camp and a tad hit and miss.

The proviso that this is an ideal seasonal read comes with the knowledge that you can have fun searching YouTube for some of the more arcane musicals in question and find out exactly what Mordden is trying to conjure before your very eyes.

His descriptions can be almost as good as the films themselves. Only the most diehard Hollywood aficionados will have seen Paramount's The Dance of Life (1929), one of the early talkies following the revolution of The Jazz Singer (actually, as Mordden puts it, "a silent with a music-and-sound-effects track"). The author describes its protagonist, performer Skid played by Hal Skelly, having to go onstage after the break-up of the central relationship: "we watch him make up in his dressing-room mirror. The black + on his eyes. The mouth extension lines. That lurid fake nose. Skelly plays the entire scene in a daze, the absurd cosmetics at war with what is happening in the story: the ripping open of a Plot B torso to reveal its broken heart".

Plot B is one of the three lines posited by Mordden for the Hollywood musical, the one where a star's ego comes between him and his girl (or her and her man). He also posits three types of audience which producers had to bear in mind: essentially urban sophisticates, in-betweeners and nostalgic hicks.

Plot B is one of the three lines posited by Mordden for the Hollywood musical, the one where a star's ego comes between him and his girl (or her and her man). He also posits three types of audience which producers had to bear in mind: essentially urban sophisticates, in-betweeners and nostalgic hicks.

Bearing which in mind, it's amazing what high-quality work evolved in the 1930s, despite the inevitable dropping of countless numbers from Broadway originals. Best were the films evolved with a free hand by Hollywood. The first of Mordden's highlights is the breathtaking Love Me Tonight from 1932, a tricky time when Hollywood was suffering from its first dip in interest in the musicals. The film is boosted not just by the presence of Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald and the collaboration of Rodgers and Hart but also by the inventiveness of director Rouben Mamoulian in the opening, "Isn't It Romantic" sequence, a token of "cinema's ability to mash time and space together".

The second peak is Shall We Dance (1937): Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, George and Ira Gershwin, Pandro Berman's classy RKO brand all conjoined in a total work of art. "The RKOs are about music - its joy, its healing power, its wonder, its enlightenment. We don't want to get too grandiose, but there's Shakespeare, there's Goethe, and there's the RKO dance musical of the 1930s". The Gershwins get a chapter of their own; so do all the great songwriters, which means no overall chronological journey - if you want it, Mordden has already devoted many volumes to the subject of the musical, and there's a neat page-long summary in the introduction.

Sometimes it's a bit of a shopping list, enlivened by Mordden's piquant turn of phrase and waspish anecdote. Occasionally you feel he's jamming in musical references just to prove his credentials to OUP. How's this for hard-to-conjure analysis: "Ager [in "Song of the Dawn" from King of Jazz] closes the first A strain in the submediant minor, then the subdominant, the dominant seventh, and the tonic but resolves the second A, hair-raisingly, in the leading-note minor-seventh (with the melody on the sixth)"....more lines follow, but I hesitate to inflict them on you.

And sometimes Mordden slips in his classical references, as when he cites, in Rosalie's choreography, "a bit of Tchaikofsky [sic] (the slow movement of the Sixth Symphony, unfortunately jazzed up a bit...)" - surely not the finale, the only slow movement? As for The Wizard of Oz's "Over the Rainbow" - bizarre candidate for cutting until the producers saw sense - no way is it "very chromatic"; in fact the main eight-bar theme is entirely diatonic (white-note).

We can all agree or disagree with many of Mordden's choices and omissions, but let's hail his accolade for the recent film version of Sondheim's Into the Woods, even if I don't agree with his statement that "it looks better in the cinema than in the playhouse, because its story is magic and so are the movies"; the theatre should create its own kind of magic, and Richard Jones's London production did exactly that. I'd also like to see mention of a flawed but fascinating Sondheim predecessor in film, Sweeney Todd, which deserved a mention if only because of the way genius orchestrator Jonathan Tunick got much of his fleshcreep into new underscoring. Pointless, though, to carp about what's not here rather than what so splendidly is; Mordden's main task, like the films he describes, is to entertain and make 'em laugh, and he succeeds splendidly on both counts.

- When Broadway Went to Hollywood is published by Oxford University Press

- David Nice's blog on the film of Into the Woods

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment